Mortality salience (MS) refers to reminders of death. Many studies found that MS can change people’s cognition and behavior. Based on terror management theory (TMT), this is because humans’ unique awareness of inevitable death, which induces existential anxiety. To manage existential anxiety, humans have evolved two defensive strategies, proximal and distal defenses. Proximal defenses cope with conscious thoughts of death. They are rational attempts to remove death-related thoughts from consciousness by suppressing such thoughts with distractions, pushing them into the distant future, or denying one’s vulnerability to death. In contrast, distal defenses are responses to thoughts of death beneath consciousness. Distal defenses implicitly influence individuals’ cognition, emotion, and/or behavior in a way that targets upholding individuals’ cultural worldviews and boosting individuals’ self-esteem. It enables individuals to believe that some valued aspects of themselves continue to exist symbolically after death. For example, MS may promote one to help others. In such a case, one may believe that his or her prosocial reputation lasts after death. Previous studies have demonstrated the effects of MS on cognition and behavior. However, whether and how MS may affect emotion (especially moral emotion) are unclear.

In February 2022, the journal, Cerebral Cortex, published a paper entitled “Mortality Salience Enhances Neural Activities Related to Guilt and Shame When Recalling the Past” by Prof. Chao Liu’s research team at the State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning & IDG/McGovern Institute for Brain Research of Beijing Normal University. This study provides psychological and neural accounts of the influence of morality salience on moral emotions.

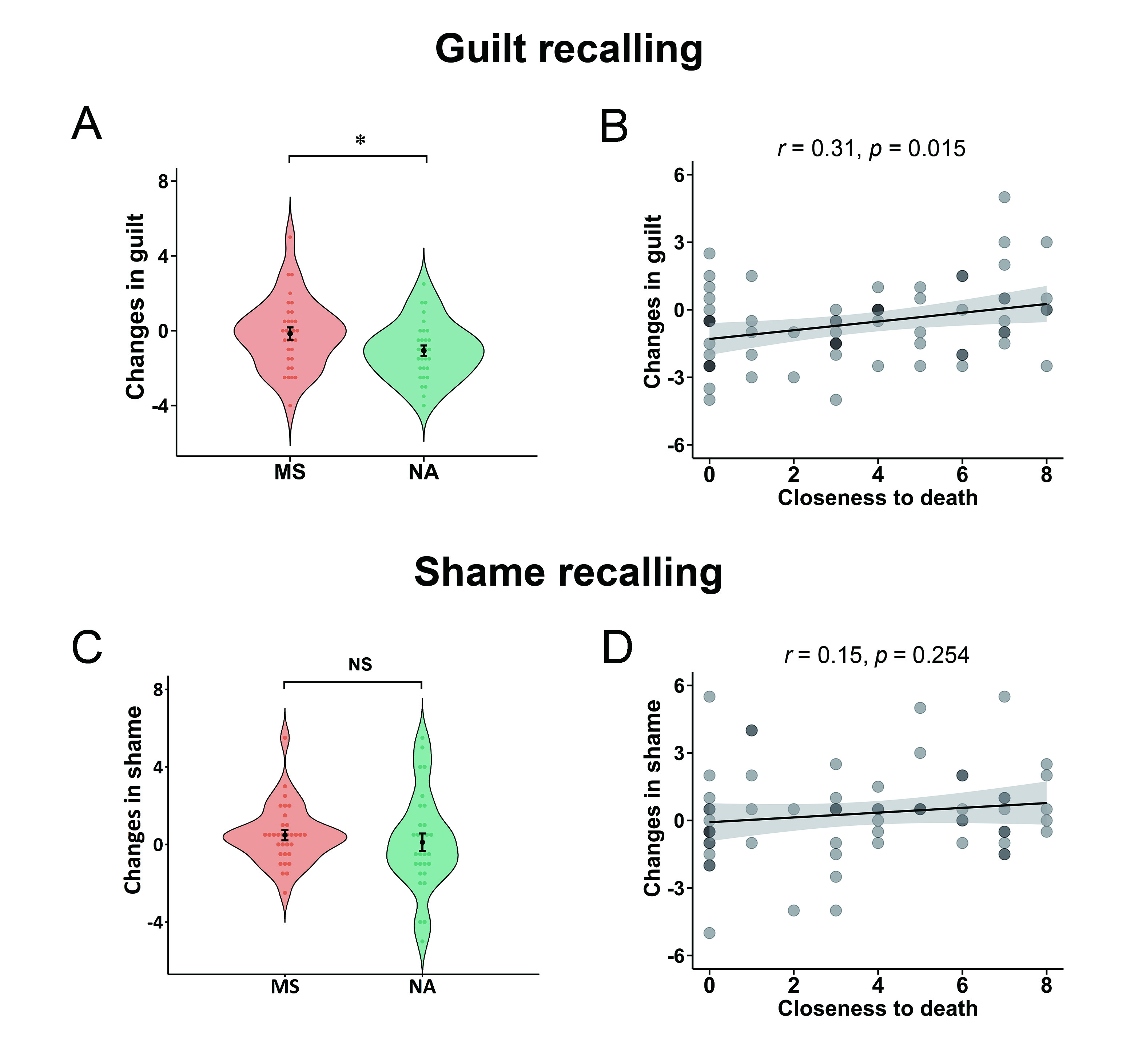

To find empirical evidence, the study investigated how MS compared to negative affect (NA) modulated guilt and shame in a later recall task using functional magnetic resonance imaging. The behavioral results indicated that MS increased self-reported guilt but not shame (Figure. 1).

Figure 1. MS increased self-reported guilt but not shame

The neural results showed that MS strengthened neural activities related to the psychological processes of guilt and shame. Specifically, for both guilt and shame, MS increased activation in a region associated with self-referential processing ventral medial prefrontal cortex). For guilt but not shame, MS increased the activation of regions associated with cognitive control (orbitofrontal cortex) and emotion processing (amygdala).

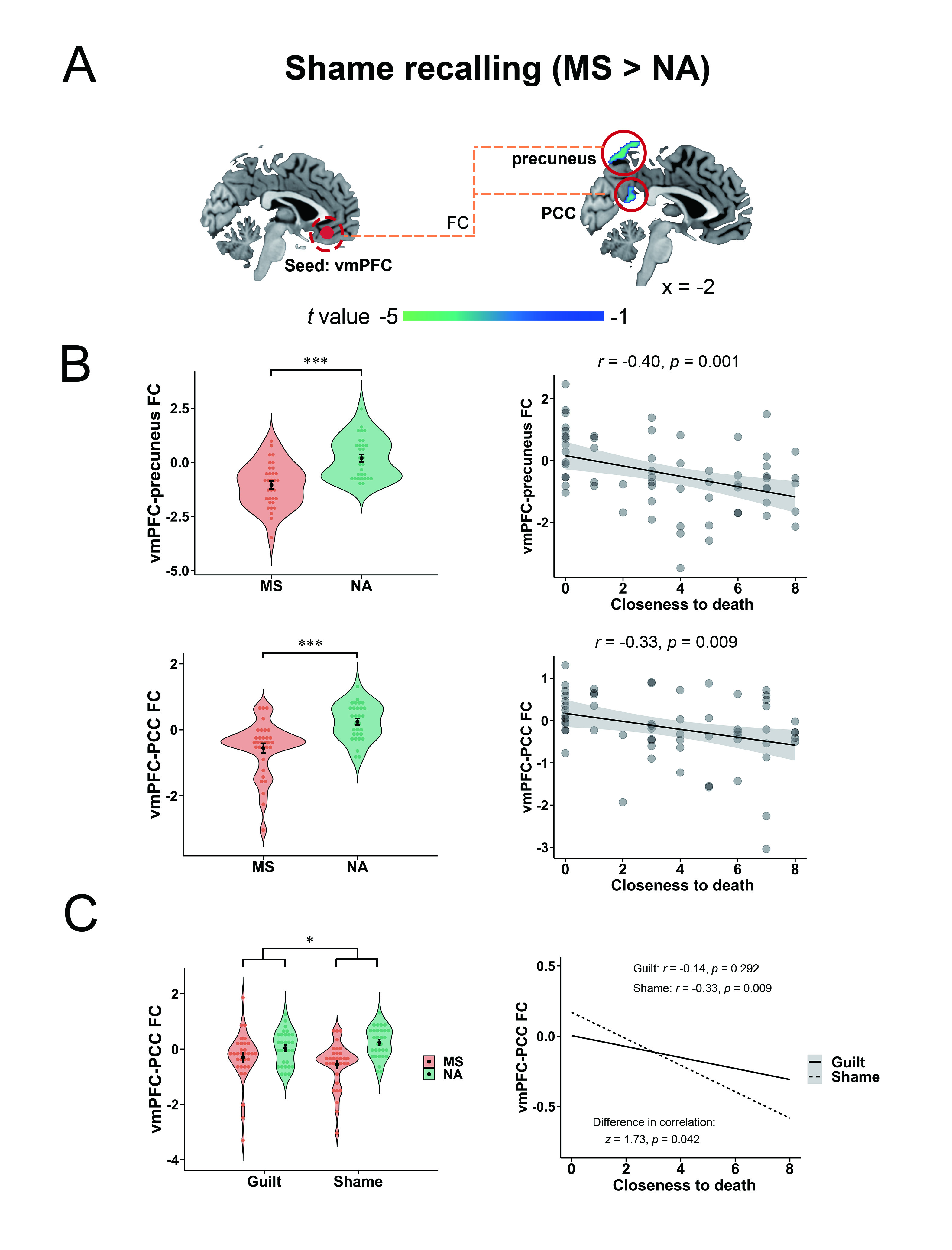

For shame but not guilt, MS decreased brain functional connectivity related to self-referential processing (vmPFC-precuneus and vmPFC-posterior cingulate cortex connectivity) (Figure. 2). A direct comparison showed that MS more strongly decreased a functional connectivity related to self-referential processing (vmPFC-posterior cingulate cortex connectivity) in the shame than in the guilt condition.

Figure 2. MS modulated functional connectivity related to self-referential processing in the shame condition.

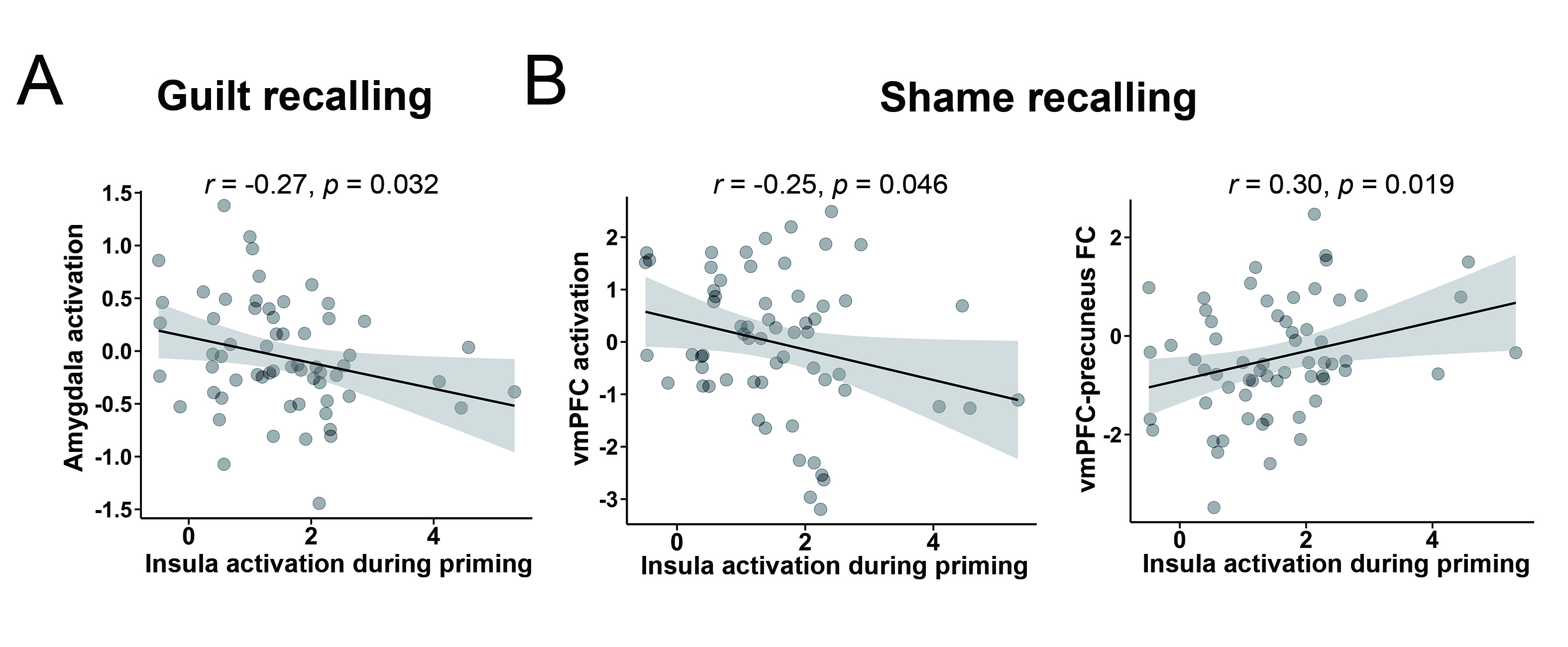

Additionally, the activation of insula during MS priming was partly predictive of neural activities related to guilt and shame in the subsequent recall task (Figure. 3). Given that the activation of the insula during the priming task is regarded as an indicator of proximal defenses and that the neural activities modulated by MS during the emotion-reliving task are regarded as indicators of distal defenses, the results show that proximal defenses are partly related to distal defenses.

Figure 3. The activation of insula during MS priming was partly predictive of neural activities related to guilt and shame in the subsequent recall task.

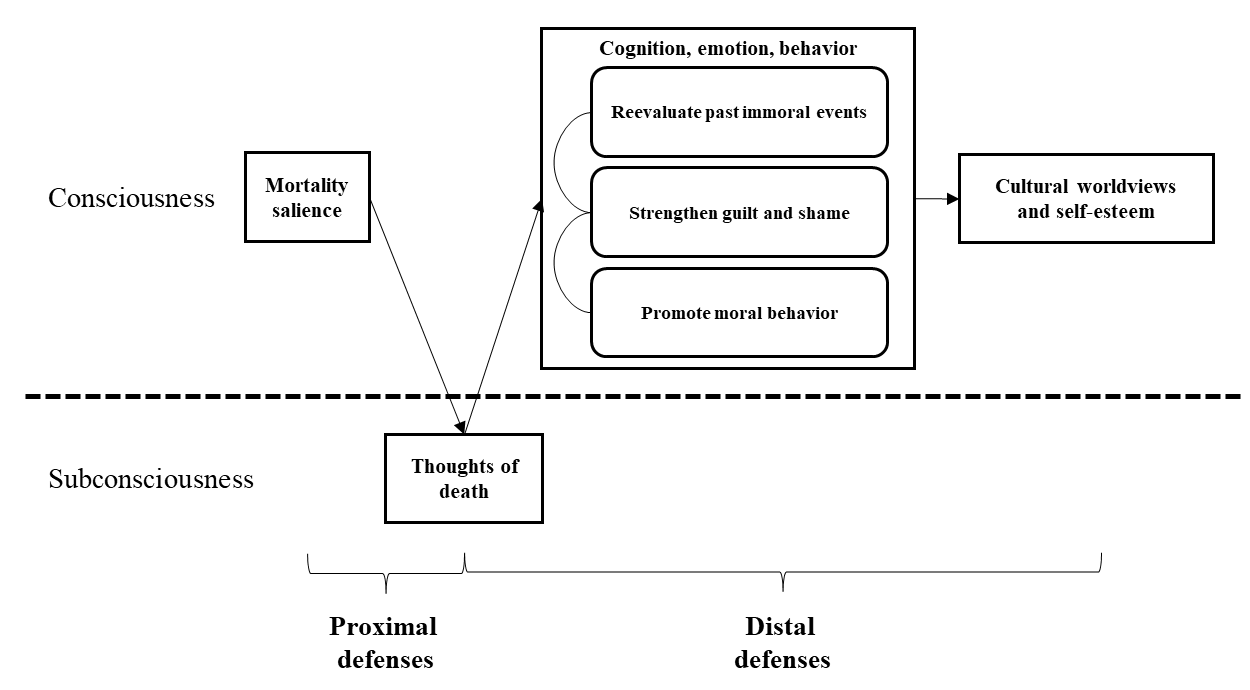

The study also completed the theoretical construction of how moral emotions are related to MS within the framework of TMT. Guilt and shame may play such roles in distal defenses (see Figure. 4). Subconscious thoughts of death implicitly facilitate individuals to reevaluate immoral events that they have engaged in and increase individuals’ guilt and shame. These two emotions prepare individuals psychologically and promote various moral behaviors (e.g., apology, compensation, or self-punishment). As moral norms are vital elements of cultural worldviews that provide a sense of order and meaning, moral behaviors can help individuals uphold cultural worldviews and maintain self-esteem in the moral aspect.

Figure 4. Theoretical construction of how guilt and shame are related to MS within the framework of TMT.

In conclusion, the study show that MS enhances subjective self-reported feelings of guilt and modulates neural activities related to guilt and shame. Proximal defenses are partly predictive of distal defenses. The study not only sheds light on the psychological and neural mechanisms of the MS effects on moral emotions but also provides new empirical evidence and theoretical insights for enriching TMT.

The authors of this paper are Zhenhua Xu, Ruida Zhu, Shen Zhang, Sihui Zhang, Zilu Liang, Xiaoqin Mai, and Chao Liu. Zhenhua Xu and Ruida Zhu contributed equally to the paper. Chao Liu is the corresponding author. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Major Project of National Social Science Foundation.

Information of the current paper:

Xu, Z., Zhu, R., Zhang, S., Zhang, S., Liang, Z., Mai, X., & Liu, C. (2022). Mortality Salience Enhances Neural Activities Related to Guilt and Shame When Recalling the Past. Cerebral Cortex. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhac004.

Other moral emotion studies of Chao Liu’s research team:

Zhu, R., Feng, C., Zhang, S., Mai, X., & Liu, C. (2019). Differentiating guilt and shame in an interpersonal context with univariate activation and multivariate pattern analyses. NeuroImage, 186, 476–486.

Zhu, R., Wu, H., Xu, Z., Tang, H., Shen, X., Mai, X., & Liu, C. (2019). Early distinction between shame and guilt processing in an interpersonal context. Social Neuroscience, 14(1), 53–66.

Zhu, R., Xu, Z., Su, S., Feng, C., Luo, Y., Tang, H., Zhang, S., Wu, X., Mai, X., & Liu, C. (2021). From gratitude to injustice: Neurocomputational mechanisms of gratitude-induced injustice. NeuroImage, 245, 118730.

Zhu, R., Xu, Z., Tang, H., Liu, J., Wang, H., An, Y., Mai, X., & Liu, C. (2019). The effect of shame on anger at others: Awareness of the emotion-causing events matters. Cognition and Emotion, 33(4), 696–708.

Zhu, R., Xu, Z., Tang, H., Wang, H., Zhang, S., Zhang, Z., Mai, X., & Liu, C. (2020). The dark side of gratitude: Gratitude could lead to moral violation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 91, 104048.